News From Dollar Country

I’m feeling much better now. In the last newsletter I was reflecting on a hard year, one of the hardest I can ever remember. After that reflection I realized how important it was for me to find a balance between my family life and Dollar Country because both are important to me. The first rule was to not keep setting deadlines for myself and so far that’s been an excellent change. My worry, as always, is that if I slow my output then my support will slow down too, but that hasn’t been the case. You all seem to like what I do enough to keep supporting it.

The biggest project that took place recently was adding location data to many of the records in the database. You can read about that in the Geographies of Dollar Country write up. It felt good to have a data entry project that I was excited about. I also picked up a project I’d dropped almost two years ago, pressing volumes 3 and 4 of my patreon lathe cut project. I press up a limited amount of tracks that are rare in my collection for the patrons to buy. I don’t really make money doing it, it’s just a fun way to share the music in the archive.

The kid is walking and babbling. I feel lucky to get to watch him grow. Being a parent is like joining a huge team of people who all experience this amazing thing, despite it being so common it also feels unique and amazing.

So the beginning of 2025 feels good. I got the screener of the Dollar Country documentary that director Michael Suter is working on last night and really enjoyed it. I can’t wait to show it to you some day, but it’s not in the final cut stage yet so I will respect Michael’s wishes and not share it despite how much I want to. I’ll also be going out on my first dig trip since before I was a parent, it feels like a big step to be away from the family for a whole day, but I had to break the seal sometime.

Cheers

Franklin

Music And Fandom

Or How For Some People Music Is Just A Phase

Music is special, it’s special for many reasons and one of them is how it differs from other forms of arts and entertainment. You can’t really have a movie be your companion, you can watch a movie, and you can love a movie, but you can’t watch a movie while you drive to the grocery store or walk to work. And it’s the same with most visual arts, using your eyes takes your attention away from the rest of the world. But music can accompany you through life while still being able to take in what you’re doing and where you are going. It’s unique that way.

There’s another, more current, way it’s uniqueness is important to us. It’s ability to be copied and shared make it special. Nearly anyone can copy music to anywhere and share it and have the copied version be nearly identical to the version the artist intended you to hear. You can copy and share movies but unless you are quite wealthy you won’t have a home theater to experience it the way the makers intended, and you can make an ultra high resolution scan of a painting but you won’t be able to see how far the brush strokes raise off the canvas or the delicate carvings on the frame. This quality of music is something we deal with every day. It allows the makers of music to be taken for granted, and for giant corporations to make millions while musicians make next to nothing. The parts of music that make it unique and amazing can also be it’s greatest flaw.

This article won’t be about that, but I had to get it off my chest because I think that is what makes it possible for music to be more important to humans than ever before and one of the least monetarily valued artforms.

And it seems that music IS more important to us than ever before. We can listen to nearly any album we want at any time without having to purchase it. But I think that music fandom, for many people, can be a phase and not lifelong.

My theory is this: some people have a time in their life when they’re interested in discovering music. In this time they find the sounds and bands they will enjoy for the rest of their lives. Once it’s over they continue to like those bands and sounds but rarely, if ever, seek out new things that sound different than what they discovered in that period. It starts around puberty and ends around the age most people would graduate from college. There’s actually some studies that back this up, kind of. Studies published by the New York Times, Rutgers, Oxford, and Harvard suggest that people have an opening in their lives where they are most interested in musical discovery, meeting more diverse sets of people, and tend to be the most open-minded and accepting. Those ages? 13-24.

Now, there’s more to it than just music. Around age 24 is also when many people start the lives they’ll lead for the rest of their days. Maybe they start a career in what they’ve studied for or maybe they start a family, but the result is that they have less time to listen to new music and go to shows. When you start doing life things that people expect of you you often have to pick and choose which hobbies you’ll have time for, if you have time for any at all.

When I worked at a record store I saw this happen in front of me. Students would come in excited about a local band or asking what records to check out, and then a few years later they would come in and ask about those same local bands and if there’s any records that sound like those records from a few years ago. Or they would come in when one of their favorite bands released a new album. Many of them stopped asking about new things to check out. Their tastes had been made and they wanted more of it, but not to be challenged. At the time I was critical, thinking that they had given up, but that’s not the case, it wasn’t good nor bad, just different.

Sometimes I wonder if I fit into these studies too. Did I develop a sound I liked in my formative years that I still search for? For all intents and purposes I’m a professional music listener, but am I still beholden to that time in my life? Despite listening to hundreds of hours of new-to-me music every year do I still only appreciate the stuff that fits that sound I learned to love then? No, I don’t think so. I think that, for some, being a music fan is a life long venture, and that’s why I can call myself a professional music listener.

With passion and time we can still learn to love new sounds and artists. I firmly believe that any form of art can be appreciated by anyone if they try. Some of the songs I’ve learned to love the most are ones I was luke warm on at first but had a fan email me and say how much they loved it. Their excitement made me revisit it and see it in a new way, opening up that appreciation in me.

This is a microcosm of life isn’t it? Sometimes it feels like the world wants us to choose what we think and never change it, no matter what. How many times have we seen a headline criticizing someone for changing their view on something? We view changing your opinion to be a betrayal instead of growth, some sort of hypocrisy instead of education and reevaluation. Sticking to our guns means that we know what we think and nobody is gonna tell us different. But I think growth and reevaluation is strength. Being able to see things from new perspectives, whether it’s music or not, has opened up new worlds of appreciation and compassion for me. Rigid things break, flexible things adapt.

So here we are, at the end of an article on something I’ve thought about daily for the past 15 years. What’s the point? What am I getting at? It’s that music holds different roles in all of our lives, but we also get to decide what role we spend in the life of music. We can choose to just let it affect us, or we can add to it. We can become active in our love for it, whether for a phase or a lifetime, always seeking out new sounds and genres. We can be active participants and then let it slide when life becomes challenging and come back to it too. The strength, and weakness, of music is it’s accessibility.

Happy listening.

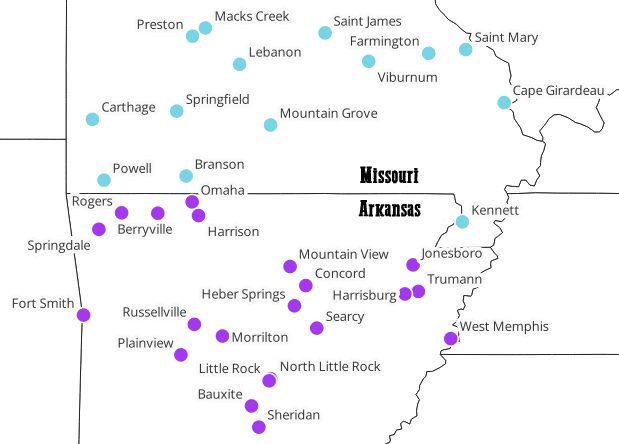

Geographies Of DOLLAR COUNTRY

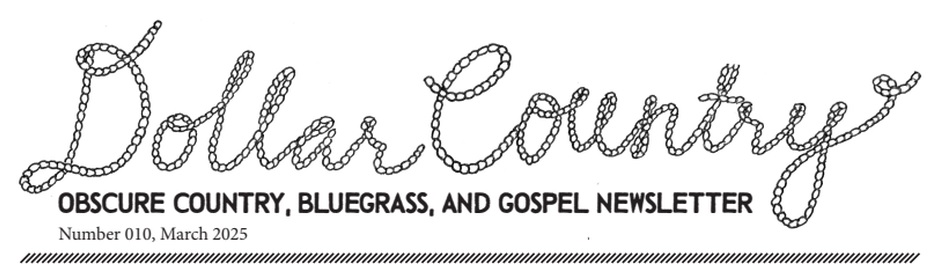

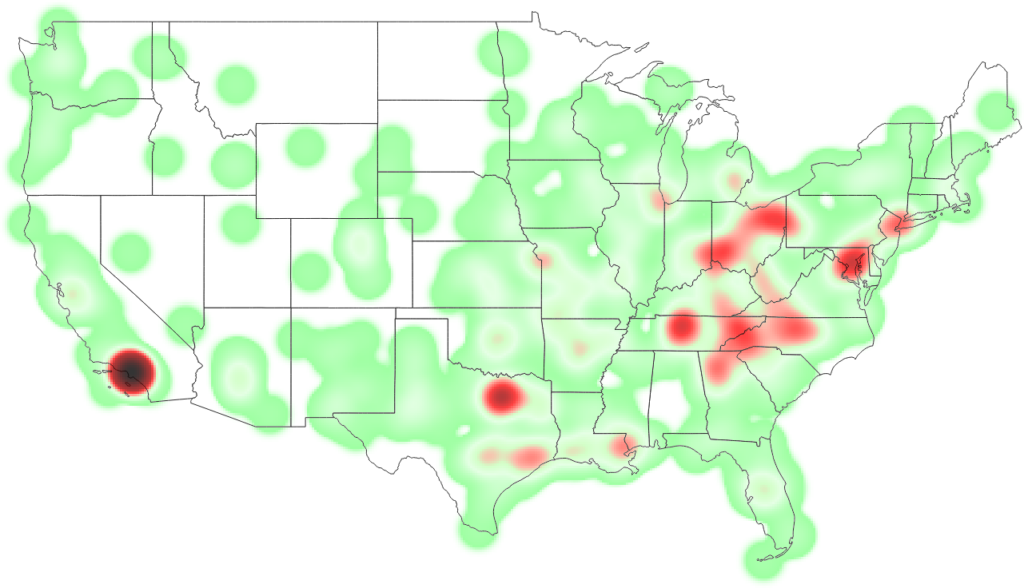

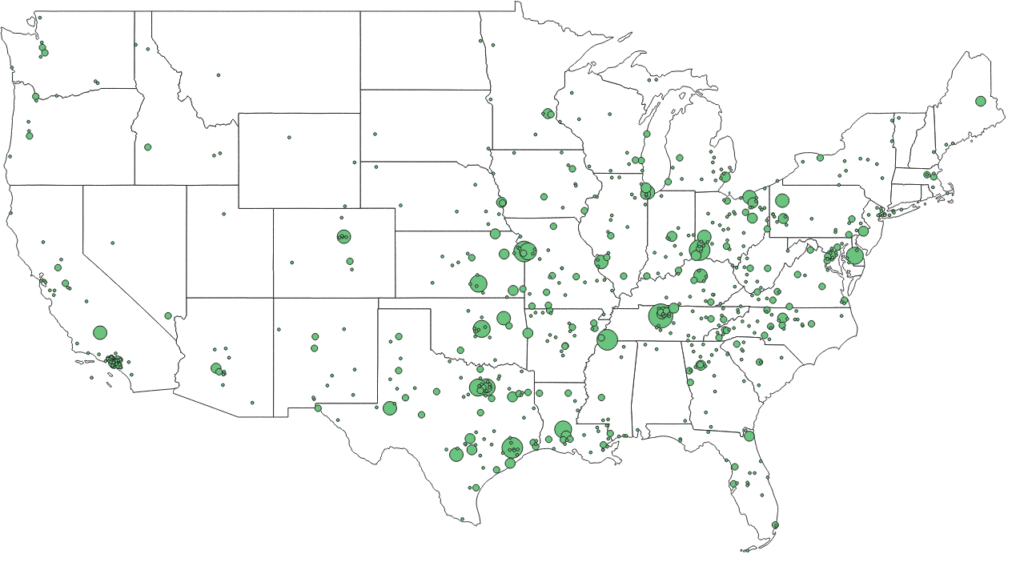

Starting in 2020 I began keeping lists on discogs of which state each of my records was from*. It was kickstarted by a goal I had to post a new record from a different state each day on instagram for 50 days in a row, so I went through each record in the collection over the course of a couple months and if it had some sort of location on the label I put it on the corresponding list. I didn’t realize at the time, but I was beginning to create a geography of Dollar Country.

Fast forward to 2025 and I finally got around to moving that data from my discogs lists to my database, tying it with each record. This may not seem important, but being able to do this allows me to visualize the data, and that is very exciting. I think this will allow for new ways for people to experience the collection and realize why it’s important. Being able to look at the records from your hometown is fun.

These points also tell a story, and with more data they will tell more and deeper stories. There’s so much more to do and I’m going to try and spend as much time entering data as I can in 2025.

This was all kicked off by my plan to do another 50 states project. I still don’t have any records from Rhode Island and I need more from Utah, Montana, North & South Dakota, New Hampshire and Vermont. If you have any records from there you’d like to donate to the Dollar Country Archive then please get a hold of me.

This project wouldn’t be happening if it wasn’t for my good friend Colin Pate who showed me how cool geography is.

* What do I mean when I say these are where records are from? Basically I find any location information I can. For most of these the location is where the label was located, for some of them it’s where the artist was based, and for others it may be a combination of those or something else. This data is only for 7” singles and doesn’t include LPs.

►Book Corner

Mamaskatch: A Cree Coming Of Age & Peyakow: Reclaiming Cree Dignity

by Darrel J. McLeod

Year: 2018 / 2021 Pages: 228 / 244

Publisher: Milkweed Editions

I’m no expert, but I’ve read more than the average North American about how colonizing Europeans treated the Indigenous people here. I know there was a planned effort to kill them with disease and to erase their culture with laws against speaking native languages, schools to re-educate their children, and governments keeping them in abject poverty. So I thought I had an idea of what I would face in Mamaskatch. I wasn’t wrong, but it was so much more.

The two books cover roughly the first half and second Darrel J. McLeod’s life. Mamaskatch is the story of his childhood and young adulthood living with his Cree family in rural central Alberta near a town named Smith. His mother, who attended government residential schools where she was punished for speaking Cree, was loving and protective of him and his siblings. Their father, Sonny, had passed away at an early age from cancer. This story isn’t sugar coated, so I won’t sugar coat it: the trauma hits early and often. Everyone in Darrel’s family has been affected by extreme poverty and the affects of government sponsored abuse. His mother becomes reliant on alcohol and their house becomes a nightmare. His sister, Debbie, gets married at 14 to escape. Darrel also leaves as soon as he can. He is shuffled between relatives until he’s old enough to have his own place, for a time living with Debbie and her husband Rory, where Rory beings sexually abusing him as an early teen.

Almost everyone in his family experiences sexual, emotional, and physical abuse from partners and family members. Through it all Darrel finds a way to make ends meet and keep a fairly stable household in Edmonton and then Vancouver. Often his apartment is where his relatives seek refuge when they’re on the outs with one thing or another. It’s apparent how much he cares about them and he works non-stop to make enough to take care of them as best he can. Mamaskatch ends with the funeral of his mother.

Both books are told in snippets. Flashes of a story here and there. Peyakow starts off with Darrel accepting a job as a rural school principal in an Indigenous community in northern Alberta. His experiences there foreshadow the rest of the book. He spends his adult life working for the government in various capacities, as a principal, treaty negotiator, and bureaucrat working with Indigenous tribes. He finds the work fulfilling but is also constantly thwarted by racism against native people, but he feels strongly that to help them there must be native representation in the government. Mamaskatch was difficult to read and Peyakow offers a lot of hope. Not everyone who has been through what McLeod has made it out alive, including members of his own family. He struggles along the way but in the end his affect on the world is measurable. Darrel helped negotiate treaties with First Nations people that gave them back rights to their land and fisheries, and was part of the negotiating group that got Canada to admit to and apologize for the residential school system.

I came away from these books with mixed emotions. When I originally posted that I’d bought them Darrel messaged me on instagram saying that he hoped I liked them. I finally picked up Mamaskatch after two years and while I was reading it I was formulating a message I would send to him when I finished. I’d never had that personal of a connection with an author I’d never met before and I was excited. As I read all the awful situations he went through I started to wonder just what I would say, everything I could think of didn’t seem to capture how I felt. One night before bed I looked him up and realized he had passed away in 2024. I felt a sense of loss about this person I’d never met. Most biographies tell you about the things a person does, but these really felt like a window into his life and emotions, I felt like I knew him. The message I was formulating in my mind would never be sent because there was no one to send them to. Thankfully he left his story for all of us. I won’t ever forget it.